How Multidisciplinary Researchers solve a problem

Published:

Introduction

Multidisciplinary research is described as a technique of research in which the tools of different sciences and disciplines are utilized to study a specific problem. In this article, examine how this is done through the multidiscplinary case of recommending contextual music. Recommendation systems are one of the most useful tools for online browsing. With huge catalogues growing everyday, a good recommendation system can save the users hours of search by directly proposing items that are likley to interest the user. This is the case for almost all online catalogues incuding merchandise, movies, books, and music. Those recommendation systems are being continously developed to accomodate the different user needs. However, each domain requires different designs based on the recommended media. Music in particular is one of the most challenging media to recommend. Music tracks are often short, spanning a duration of few minutes, yet quite complex in their content. People often spend hours listening to music one track after the other. While users have their own listening preferences, they could also enjoy exploring new styles. Hence, music recommenders are designed to provide fast and coherent items, while also infusing new items for exploration. All while being personalized to each user. A pretty complex task.

To make it even harder, music as a media is one of the most influenced by the user situations/conditions, specially since the development of portable music players. We listen to different music with friends than when we are alone. We listen to different music when we are sad than when happy. We listen to different music when doing sports than when studying. This long list of influencing situations can keep on going. Researchers at a crossroad of psychology, information retrieval, and machine learning have been trying to identify these influencing situations and its effect on the listening preferences and music content to help provide better recommendations.

Crossroad of domains

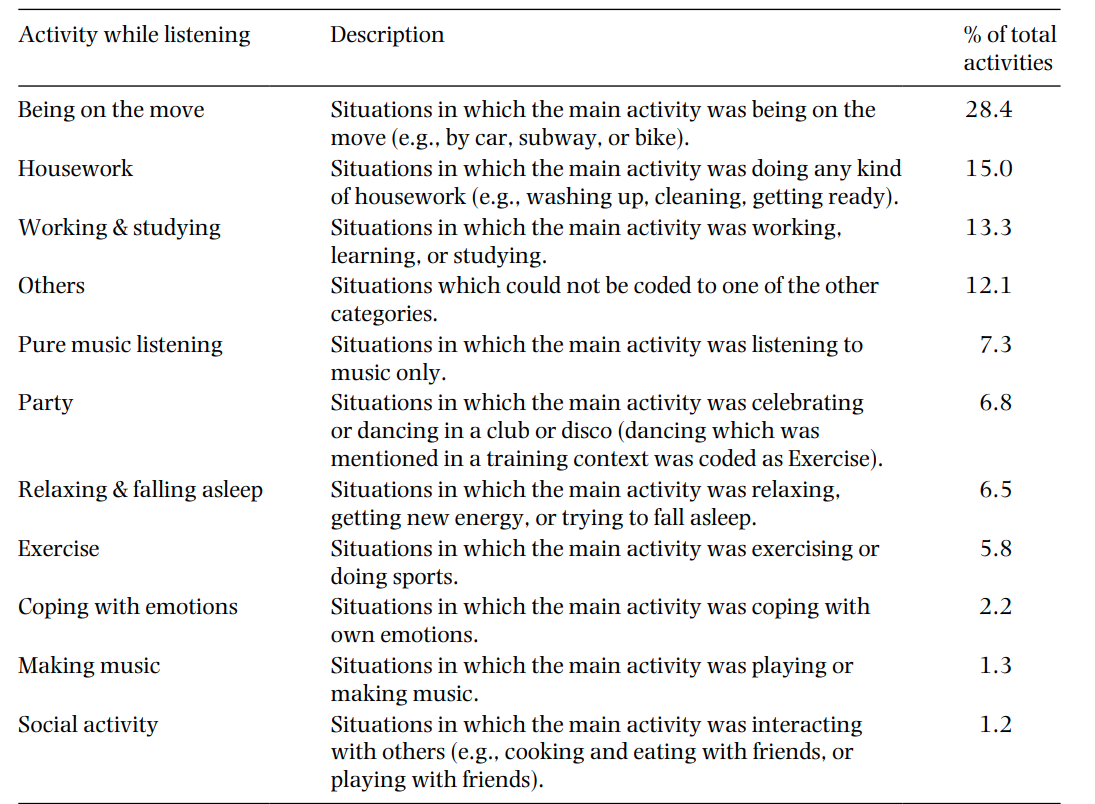

In the psychology domain, researchers focus on understanding how people use music in their daily life. They try to understand how much of our daily engagement with music is attributable to individual characteristics and how much it depends on the listening situations, and what are these situations. Early before the progress in information retrieval, they identified the influence of the listening situation on the listening preferences and tried to categorize it. For example, situations could be categorized as either environment-related or user-related. Environment situations reflect the location, time, weather, the season, among others. While user situations included the user activity, mood, social setting, etc. These situations are still independent from the listener’s personal preferences shaped by their personality and culture, which is also a research question being studied. Those studies enable us to narrow down the potential situations and study their impact on our preferences. As an example, the following table shows the results from one of the studies [1] indicating the frequency of different situations that influence the listening preference.

Example of music listening situations and their frequency of occurance from a study by Greb et al. [1]

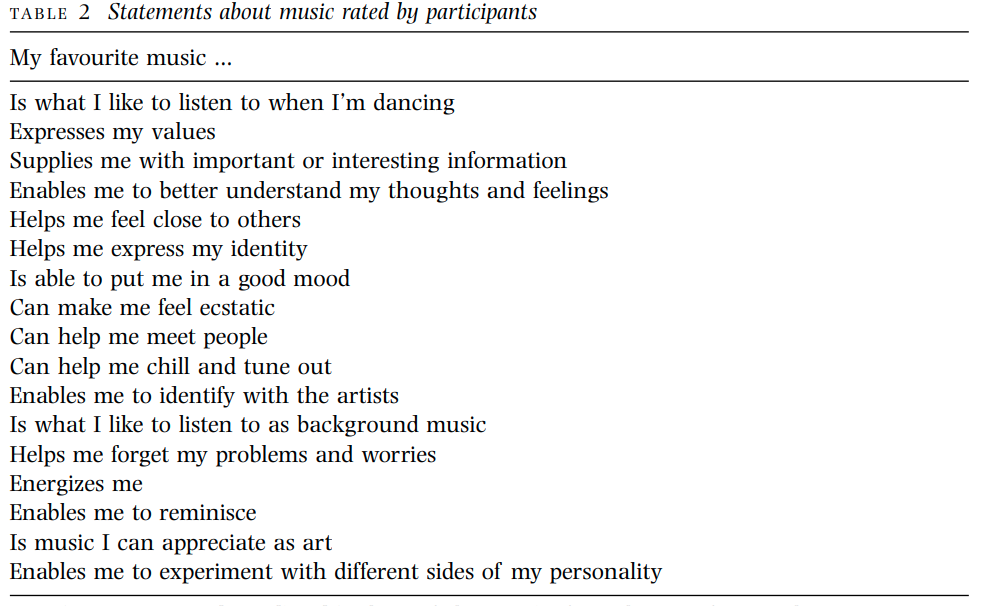

Another dimension of studying music daily use is understanding the listening intent. The intent refers to a specific function of music that the listener is seeking. While the listening intent can be influenced by the situation, it can also be different in the same situation. Understanding the listening intent can help us understand the music style/content the listener is seeking. An example of different functions of music reported by listeners in one of the studies [2] can be found in the following table. While these studies show the level of complexity in selecting music, it helps to narrow down the problem to tangible factors. For those interested in this line of research, here are some references for further readings [1,2,3].

Reported statements of participants on their intent from their favorite music. From a study by Schäfer et al. [2]

However, to properly study this influence on the music content, we needed to make progress in information retrieval tools.

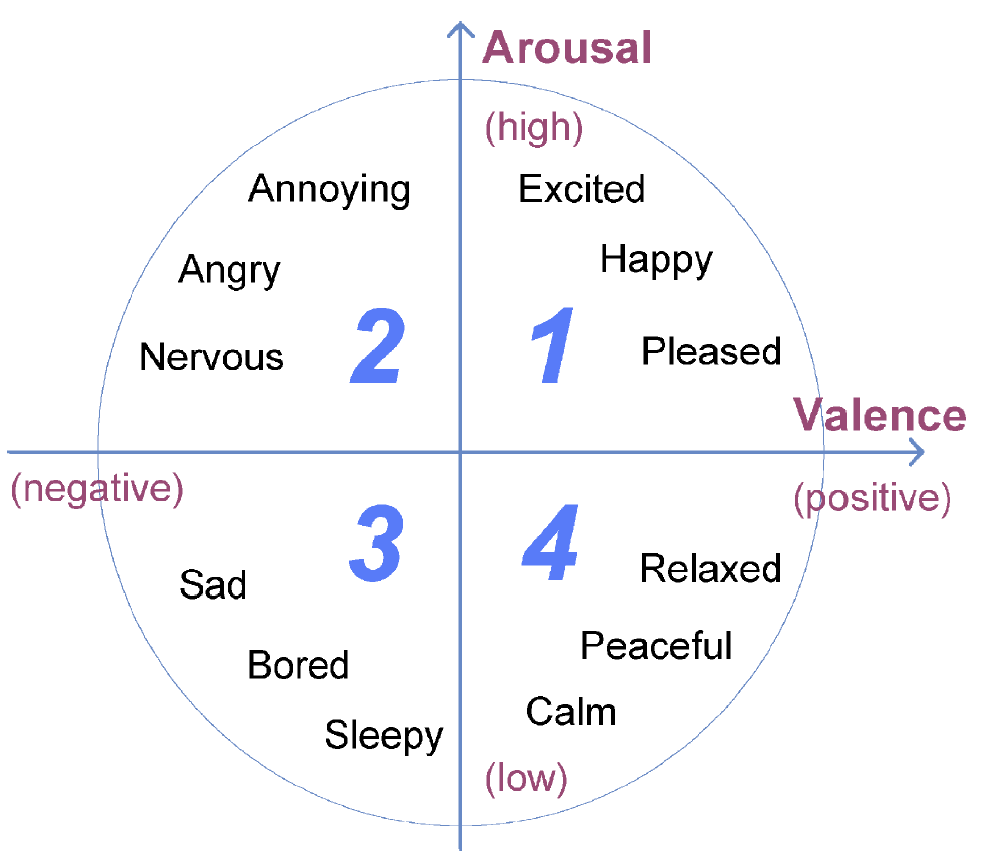

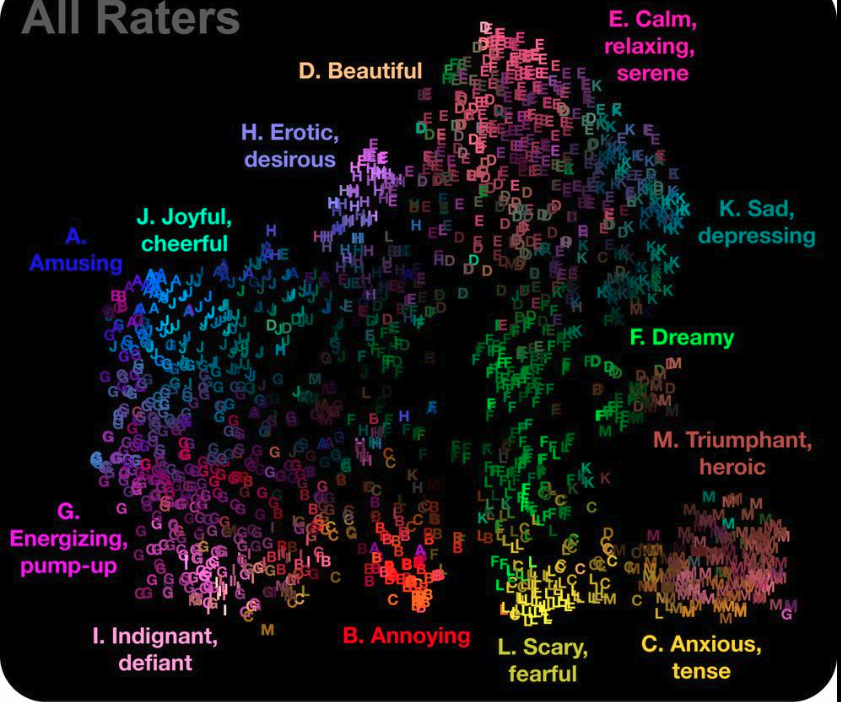

In the information retrieval domain, researchers have been working on analysing the music content and finding means to describe and categorize it. One of the prevalent descriptors of music is what is called the valence-arousal scale. This scale enables us to narrow down a “music purpose”, i.e. the function of a music piece, by describing its emotional effect through two dimensions: arousal and valence. Researchers develop intelligent models that can rate a music piece on this scale by analysing its audio content. The figure below shows this valence-arousal space. However, this is among the simpler ways of describing music through only two descriptors. More complex methods rely on embedding music, either through content similarity or through frequent cooccurances, into a high dimensional space. This representation enable us to describe and explore music through more abstract features. While less interpretable, those represetnation embeddings have proven to be a useful tool to describe the content of the music based on certain criteria. An example of an embedding space projected down to 2-d showing how similar music is clustered together is shown in the figure below. Another way, we recently proposed, is to learn this representation for the music according to each user independetly, to learn how different listeners use the music [4]. Now that we have a proper way to represent and retrieve music through its content, and have an idea of how listening preferences are influenced by different factors, we can put our finding in use to provide contextual recommendations!

The Valence-Arousal scale. Figure from Du et al. [5]

Visualization of music representation and their reported feelings by Cowen et al. [6]

Finally, in the machine learning domain, researchers have been trying to develop intelligent systems that take all this different factors in consideration and provide relevant and timely recommendations. With such complex requirements, studies have been proposing newer more sophistcated recommendation systems continuously. While we will never have the space to describe all of them, here are some examples of both specialized contextual recommenders and generic recommenders. From specialized recommenders, one approach [7] uses the emotion descriptors to match music to places-of-interest, which could be of use for a mobile travel guide. A more complex and generic contextual system uses all data available in an online streaming service to predict the content of a new listening session [8]. This system considers both the current user situation, through the used device and time of the day, and the user’s listening history and global preferences to retrieve tracks most suitable for the new session. These tracks are represented in an embedding space similar to the one described earlier. These models are trained on millions of data samples and different users to better learn how to model a contextual session for any user. Those more interested in contextual recommendation systems can refer to this detailed review [9].

Conclusion

In this article, we explored how one very common problem requires efforts from many different domains put together to tackle it. This is multidisciplinary research.

References

[1] Greb, Fabian, Wolff Schlotz, and Jochen Steffens. “Personal and situational influences on the functions of music listening.” Psychology of Music 46.6 (2018): 763-794.

[2] North, Adrian C., and David J. Hargreaves. “Situational influences on reported musical preference.” Psychomusicology: A Journal of Research in Music Cognition 15.1-2 (1996): 30.

[3] Schäfer, Thomas, and Peter Sedlmeier. “From the functions of music to music preference.” Psychology of Music 37.3 (2009): 279-300.

[4] Ibrahim, Karim, et al. “Should we consider the users in contextual music auto-tagging models?.” International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR). 2020.

[5] Du, Pengfei, Xiaoyong Li, and Yali Gao. “Dynamic Music emotion recognition based on CNN-BiLSTM.” 2020 IEEE 5th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC). IEEE, 2020.

[6] Cowen, Alan S., et al. “What music makes us feel: At least 13 dimensions organize subjective experiences associated with music across different cultures.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117.4 (2020): 1924-1934.

[7] Kaminskas, Marius, and Francesco Ricci. “Emotion-based matching of music to places.” Emotions and Personality in Personalized Services. Springer, Cham, 2016. 287-310.

[8] Hansen, Casper, et al. “Contextual and sequential user embeddings for large-scale music recommendation.” Fourteenth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. 2020.

[9] Lozano Murciego, Álvaro, et al. “Context-Aware Recommender Systems in the Music Domain: A Systematic Literature Review.” Electronics 10.13 (2021): 1555.